Fortunately, debates over which style of martial art is ‘the best’ have become less and less common. Professional Mixed Martial Arts competition has driven home the point Bruce Lee was making decades ago; Being unwilling to adapt and integrate means the lid on the coffin is closing. However, with the increase in popularity of “Reality-based” training, the old Sport vs. Street argument is ever-present.

It would be tough to count the number of times I’ve heard some variation of the following statement:

“That won’t work on the street! People don’t fight like that.”

Is this simply one of those cliches leveled by martial artists at other systems or schools to prove why their way is superior? Or is it a valid criticism in at least some cases?

The streets are filled with people who cover the entire spectrum of fighting skills and proclivity for violence. Professional boxers, BJJ black belts, Soldiers, Policemen, Gang bangers, Drug addicts, and Predators of all colors and stripes share the same streets as you and I do.

Often what’s meant by the above statement is either;

- That fine motor skills are lost, or at the very least heavily degraded under acute stress, and/or;

- There’s a good chance you won’t see the attack coming.

It’s certainly true that the more violent the encounter, the less skill is usually involved. Therefore the ‘skilled responses’ that we sometimes train against (a well executed straight punch or crafty defensive maneuver for example) are not “realistic”. Add to that the fact that most martial arts training is conducted as if to prepare the student for a duel; shoes removed, wearing ‘workout’ attire and squared off with a single opponent who is likewise dressed for the gym and unarmed.

Some very good instructors I know stress the difference between getting into a fight and being the victim of an attack. Fights sometimes begin with two people facing off and ample warning; Maybe not the ones we have to worry about as expert martial artists (ha!), but certainly those involving young males and alcohol, women, or some combination of both. Attacks on the other hand usually happen without warning. The attacker is not looking for a fight; He wants to achieve his objective and get away before men with guns and badges show up. Worse yet, there will probably be weapons and/or multiple persons involved.

As generalizations go, the previous paragraph is a pretty good one. It certainly helps to remind ourselves to think beyond the ‘dueling’ mindset. There is however, one caveat: Reality is highly unpredictable.

I taught a gentleman who works at a correctional facility in Southern California. He related to me that most instances of violence against the staff involve skilled attacks. Inmates are sharing the martial arts training they received on the outside with one another. Officers confiscate makeshift training equipment on a regular basis. Wrap a pillow around a phone book, tie it to your arm and you’ve got an effective Thai-style striking pad.

Rather than generalizing or speculating about what type of attack will be used against us should we be attacked, or throwing around a bunch of statistics on street fights, I’ll pose what I feel is a pertinent question that’s not asked nearly enough. Are there key principles we can focus on in our training regardless of which art we study, to maximize effectiveness when facing any threat, be it a fight or an attack scenario? I believe there are. This article is an attempt at describing and organizing those principles, as well as providing a few drills that you’ll hopefully find useful.

MINDSET

One of the main lessons lessons I’ve learned from my teachers in the martial arts is the importance of mindset. Most anyone can, through training, develop a combative mindset. We may not all be warriors, but this is an area with potential for vast improvement among martial artists. We’re going to focus on two aspects, awareness and attitude.

1) AWARENESS

Needless to say, it’s tough to counter an attack you don’t see coming. Awareness puts you in a position to respond, both mentally and physically. A prerequisite to making any self defense method effective is having knowledge about what’s happening in the world around you. Without it, nothing else matters.

2) ATTITUDE

The idea of “having an attitude” usually carries a negative connotation, but when it comes to fighting it’s absolutely critical. When I speak of attitude, I’m talking about three things primarily:

Acting with intent

Sloppy technique executed with “emotional content” usually beats perfect technique done half-heartedly. Put simply, emotional content equals intent. We decide on a course of action and perform that action with maximum effort, holding nothing back. In a self-defense situation, when our life, or the lives and well being of others are on the line, our intent has to be to cause enough harm to stop the threat. Escape and/or evasion aren’t possible, therefore violence must be countered with violence.

Having an accurate perception of our own self-worth

My life and well being are worth defending, as are yours. Never hesitate to use force to defend them. This would seem to be a no-brainer, but as any experienced martial arts instructor can tell you, it’s an area where many people have issues, and often they aren’t aware of them.

Having confidence in our abilities

Effective training gives us the confidence to know that our skills will work when the time comes to use them. For those with low self esteem, a lot of physical training may be required to overcome it.

Proper mindset plays a huge role in dealing with what we’re about to discuss, which may be the most dangerous element of any confrontation on the street.

DEALING WITH AGGRESSION & RETURNING AGGRESSION

One critical concept related to self-defense that often goes unmentioned is unequal initiative. The first person I heard speak at length about it was Craig Douglas. Most of us have little desire to get involved in any sort of conflict. We just want to go about our business. Someone who has decided to rob or steal, driven by a chemical addiction for example, is operating on a completely different level. Even the rowdy drunk guy in the bar looking to pick a fight has probably amped himself up pretty well prior to approaching his mark. The result is that we’re very suddenly going to be faced with a lot of physical and verbal aggression with little or no chance to prepare for it.

Let’s look at a few drills that I believe will help develop the ‘aggression switch’ that you need to deal with and counter those sudden bursts of violence.

F.O. Drill

In the late 1970’s, one of Dan Inosanto’s students by the name of Bob Ward was working as a strength and conditioning coach for the Dallas Cowboys. Through Mr. Ward, Guro Inosanto and a small group of his students including Larry Hartsell, Jerry Poteet, and Tim Tackett brought functional martial arts techniques and training methods to the National Football League. Sifu Tackett shared a drill with us in his training group that he used with the pro football teams. The purpose was to get guys with a calmer temperament in the mindset of hitting hard.

- Form a circle

- Coach starts the drill by shoving the person closest to him while yelling “F**k you!”. The more aggressive the better.

- The player shoves back, then repeats the scenario by shoving the next closest person to him/her. The coach can tell right away what kind of players he’s dealing with. It’s a good thing if the drill gets out of hand.

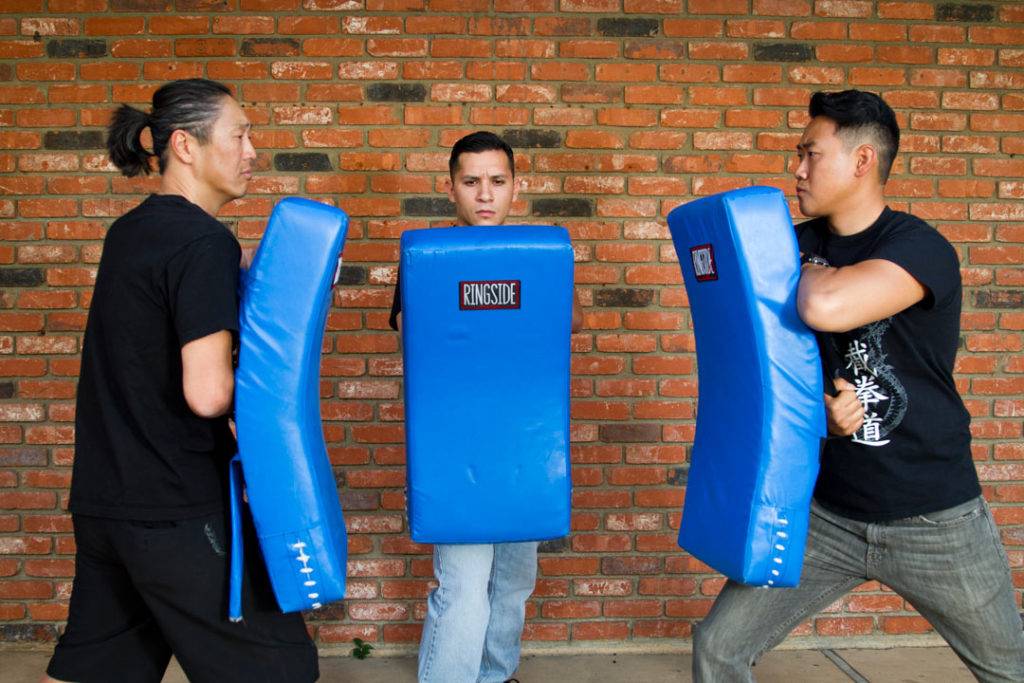

Mountain Goat Drill

No matter how great our technique, physical strength matters. It’s crucial that we learn how to take full advantage of what we’ve got using leverage, and most of all, be able to apply it under pressure against an opponent of equal or greater strength.

The mountain goat drill is nothing more than a head-to-head drill, literally. The goal is to drive your partner backward through sheer force and leverage without using your hands.

Phone Booth

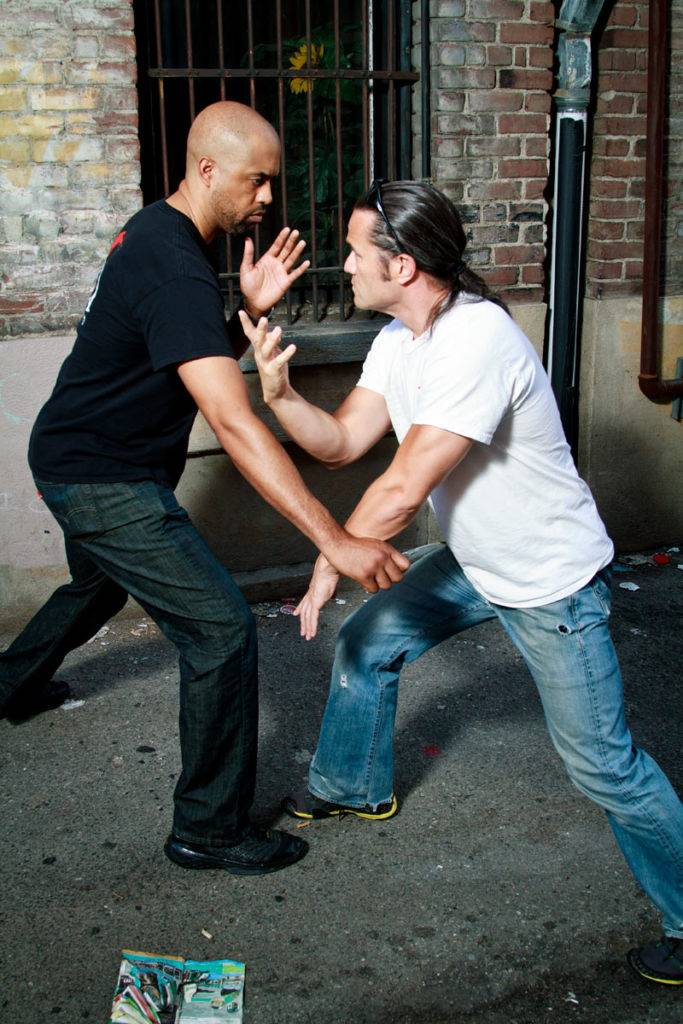

Standing in line at a store, going to a concert, or walking through any generally busy area means other people are going to get close to you. An attacker that knows what he or she is doing will take advantage of those small trespasses into our personal space that we all allow out of common courtesy. Adding to that, probably the most shocking statistic I’ve found is that more people in the United States are murdered each year during an argument with an acquaintance than in the commission of any crime (FBI Uniform Crime Reports 2012). That means we must learn to defend ourselves from the range in which we typically hold a conversation with people that we know.

For this drill, using whatever equipment or barriers are available, we create a space approximately the size of a phone booth and put two people inside of it. On the trainers command, they fight all out at close range for 5 to 15 seconds or until the trainer calls time. It’s important that the students are not allowed time or opportunity to prepare.

The point I’m making here is if you can’t deal with the initial burst of aggression from an attacker, you won’t survive. Knowing yourself and your own limitations is crucial.

LOSS OF FINE MOTOR SKILLS & EFFECTIVENESS OF SKILL TRAINING

What’s not often mentioned is that while fine motor skills may go out the window during an extremely violent confrontation, the attributes developed through ‘skill training’ do not. A boxer’s hand speed is not going anywhere. The MMA fighter’s elite strength and conditioning isn’t either. Most certainly the professional Soldier is not going to lose the combative skills and mindset acquired through years of intense training because some knucklehead is accosting him or her outside of a bar.

As martial artists, it’s our job to find out at what point our techniques break down into gross movements and train in a way that minimizes the loss of fine motor skills. One way of finding out where exactly those skills break down is to video record ourselves sparring with varying levels of speed and power and analyzing the results. We would typically separate each variable in to three levels of intensity and then mix and match.

For example:

High speed / Medium power / vs. 1 Opponent

Low speed / Low power / vs. 2 Opponents

After running these sparring exercises the saying “speed kills” really proves itself to be true. The speed of an encounter has great effect on the loss of fine motor skills. One guy moving very fast is harder to deal with than two guys moving slow. Perhaps the most important lesson to be learned from this is that it can be turned around on an attacker and used to completely change the dynamic of a confrontation.

SPEED & REACTION TIME

We aren’t all gifted with amazing physical speed, but we can all reduce the amount of time it takes us to react. We do that simply by eliminating unnecessary options.

There are several contexts in which reaction time can be measured. The “Handbook of Perception and Action: Motor Skills” defines them as:

- Simple reaction time – The time required to perform one predetermined action based on a stimulus

- Choice reaction time – The time required to perform one of multiple possible actions based on a stimulus

- Go/No-Go reaction time – Choosing whether or not to perform one of multiple possible actions based on a stimulus

In short, the more choices there are to be made, the slower the overall reaction time. An “expert” will instinctively preselect an action to be taken, making them faster than the “average” person. Bruce Lee was a huge proponent of training a limited number of responses to any given attack. In his art of Jeet Kune Do, it’s referred to as the principle of daily decrease.

The idea behind daily decrease is that it’s ideal to “own” a few techniques, refined to such a high level that your responses are automatic and happen without thought.

“When there is an opportunity, I do not hit. It hits all by itself.”

Bruce Lee (Enter the Dragon)

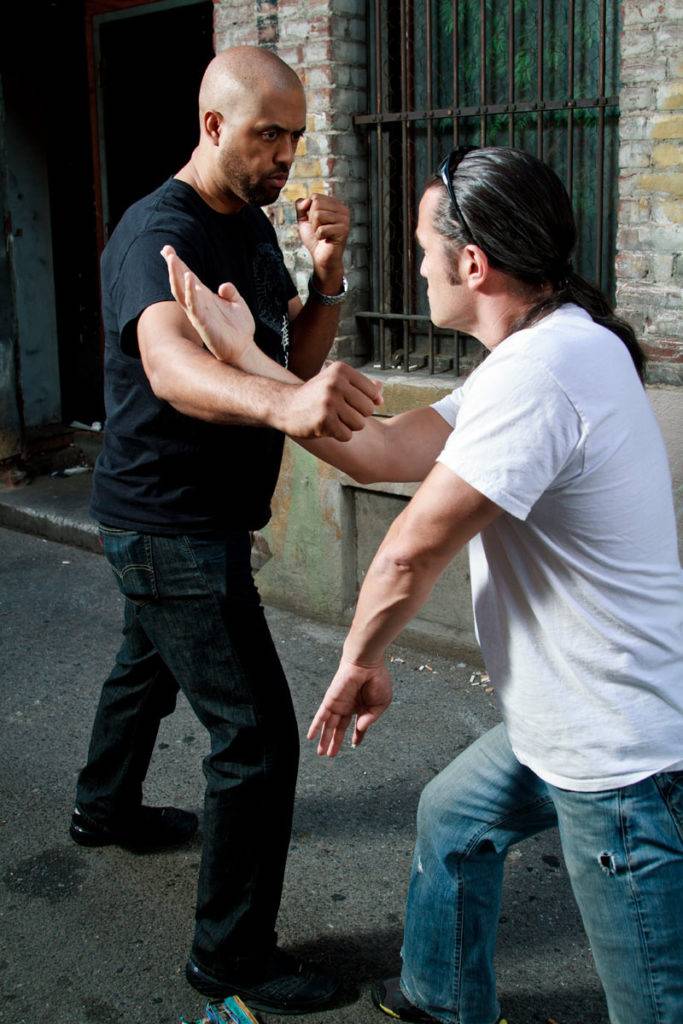

SIMPLE IS FAST

To be truly street effective we need to have one response that will cover many scenarios and can be drilled over and over until it becomes a simple reflex. Being able to fall back on this single technique increases reaction speed and thereby our chances of surviving the most dangerous part of the fight, the first few seconds. We all freeze when faced with danger, what matters is how quickly you can recover and start doing something.

There are many options for a one-size-fits-all response taught by some great martial arts instructors. I included a few of them in a previous article titled High Performance Sparring. The one that I’ve found to have the greatest effectiveness for myself is the simultaneous high/low cover that I learned from D.m. Blue, the most senior active member of the JKD Wednesday Night Group.

“Most martial arts that are any good focus on a few things done well.”

Tim Tackett

Which technique you choose isn’t important, so long as it meets a few simple criteria. It needs to work under less than ideal conditions, whether executed perfectly or not, against a blade, impact weapon, and the empty hand. If it works well against a punch but gets you stabbed by a training partner concealing a knife, find something else. There are many options.

In summary, cultivate awareness, develop an aggression switch, know your limits, and keep it simple.